Understanding Financialization

In today's world, the term 'financialization' describes a profound shift where the economy's heart has moved from the tangible creation of goods and services to the manipulation and trading of financial assets. This chapter examines how this transformation has subtly yet profoundly altered societal values, leading to an erosion of love and human connection. Here, we propose that as financial gains have become the primary focus, the essence of love—empathy, community, and personal relationships—have been marginalized.

The Economic Transformation: Once, the economy was about producing physical goods or providing services; now, it's often about managing, trading, and speculating with stocks, bonds, derivatives, and other financial instruments. This shift has placed financial performance at the forefront of corporate and personal goals, often eclipsing the value of human interaction and community development.

Creation (Historical) vs. Financialization (Modern)

The Industrial Era - Wealth Through Creation

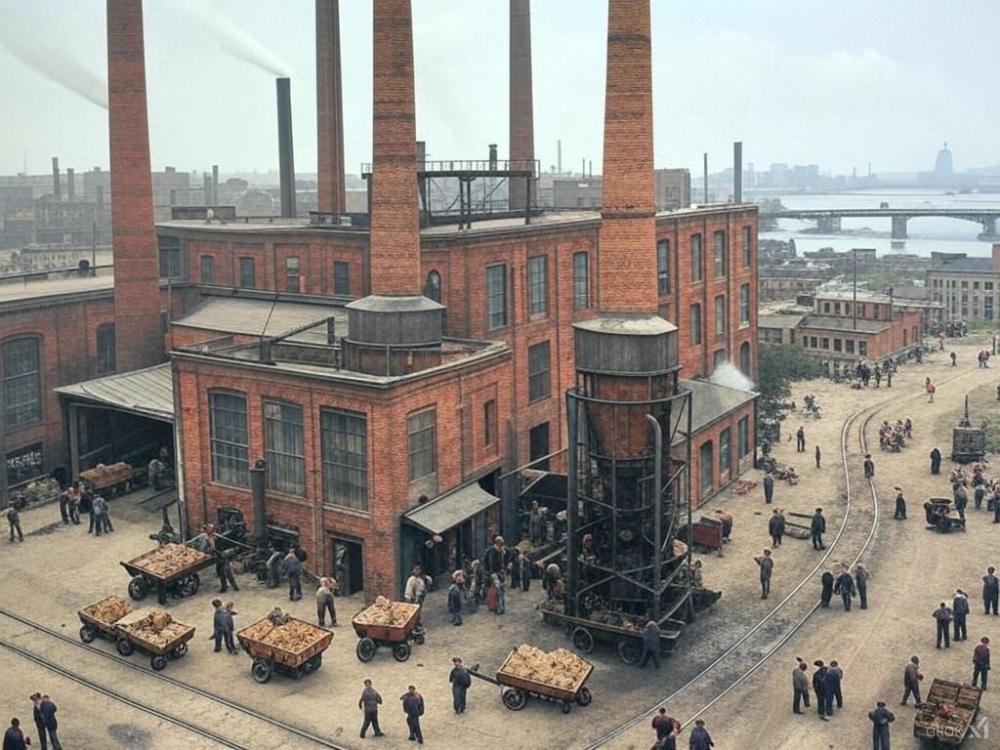

Physical Production: In the 19th and much of the 20th century, wealth was predominantly generated through tangible production. This era was marked by the establishment of factories, the invention of new machinery, and the growth of industrial crafts. Wealth creators were often those who could innovate in manufacturing, agriculture, or infrastructure, leading to products and services that directly improved living standards or facilitated further economic activity. Figures like Andrew Carnegie (steel), Henry Ford (automobiles), and Thomas Edison (electrical innovations) became symbols of wealth because they transformed industries through invention and production. Their wealth was a direct result of creating value that had a physical or service-based outcome.

Value of Labor: The labor of workers in factories, mines, or fields was central to this model. It was through their hands that raw materials were turned into products, and their labor was directly tied to the wealth of the industrialists. This period valued craftsmanship, innovation, and the physical expansion of economic capabilities.

The Modern Era - Wealth Through Financialization

Financial Engineering: Today, wealth accumulation often involves what can be termed as 'financial engineering'—a process where wealth is created or increased through the manipulation of financial assets rather than through direct production.

Financial Instruments: Wealth is now frequently generated through trading stocks, bonds, derivatives, and engaging in complex financial transactions like mergers, acquisitions, or leveraging debt. The focus is on financial strategies that can manipulate market perceptions, valuations, or exploit market inefficiencies.

Speculation and Trading: Financial markets have become arenas where wealth can be amassed quickly through speculation—buying and selling based on predictions about market movements rather than the intrinsic value of the underlying assets. High-frequency trading, algorithmic trading, and investment banking practices exemplify this shift.

Devaluation of Traditional Labor: This transformation has led to a cultural shift where the skills in financialization are often prized over those involved in physical production or service delivery.

Impact on Workers: The devaluation is not just symbolic; it has real-world implications. Manufacturing jobs have declined in many Western economies, with financial services becoming a larger part of GDP. This can lead to a disconnect where those engaged in traditional labor might feel their contributions are less valued or rewarded compared to those in finance.

New Wealth Elites: The modern wealth creators are often those who can impact financial markets. This includes hedge fund managers, investment bankers, and financial traders, whose wealth might not correlate with tangible production but rather with their ability to understand and exploit financial systems.

Cultural and Economic Shifts: This change from creation to financialization has broader implications:

- Risk and Volatility: Wealth based on financialization can be more volatile, as seen in economic crises like the 2008 financial crash, where wealth was built on speculative bubbles.

- Economic Inequality: The skills and access required to understanding and prosper though financialization are not as widely distributed as those for traditional labor, potentially increasing economic disparities.

- Focus on Short-Term Gains: There's a cultural shift towards valuing quick, often short-term financial gains over long-term, sustainable economic development or community-building efforts.

- Reevaluation of Value: This section calls for a reevaluation of what we consider valuable in economic terms. While financial innovation has its place, there's a need to balance this with the recognition of wealth generated through tangible creation, innovation in goods and services, and the labor that supports these endeavors.

In summary, the journey from wealth through creation to wealth through financialization reflects a profound change in the economic landscape, one where the mechanisms of wealth generation have become abstracted from physical goods and services, often leading to a devaluation of the labor and creativity that once defined economic progress.

Financialization and the profound effects on values and human dignity.

Decline in the Value of the Dollar

(click to see value of dollar from 1900 to today)

Inflation and Speculative Bubbles:

- Asset Inflation: Financialization has led to an increase in speculative investments in assets like real estate, stocks, and commodities. This often causes price inflation in these markets without corresponding increases in real economic value or productivity, which can lead to a general devaluation of the currency as more money chases fewer goods or assets.

- Currency Devaluation: When financial markets inflate asset prices, central banks might respond by increasing money supply or lowering interest rates to stimulate or stabilize the economy, actions which can lead to currency devaluation over time.

Shift from Productive to Financial Investment: Money that once would have gone into physical capital, infrastructure, or R&D is now often directed towards financial markets looking for quick returns. This reduces the real economic output per dollar, contributing to dollar depreciation as less tangible value is created.

Global Financial Dynamics: The dominance of financial markets has made currencies like the dollar more susceptible to global financial flows. When investors move capital out of dollars into other currencies or assets, this can weaken the dollar's value.

Reduction in Dignity for Honest Work

Wage Stagnation and Financial Sector Growth leading to Income Disparity: While financial sectors have seen significant growth and wage increases, wages in sectors involving manual or service labor have often stagnated or grown much slower. This disparity erodes the dignity of work when honest labor does not yield a living wage.

Automation and Outsourcing: The focus on financial efficiency often leads to automation or outsourcing of jobs to reduce costs, diminishing the value and respect for traditional, hands-on work.

Cultural Shift in Value Perception leading to Financial Success Over Honest Labor: With society increasingly valuing financial acumen over the skills required for traditional work, there's a cultural devaluation of jobs that involve physical or service-based labor. This shift can lead to a perception that such work is less valuable or prestigious.

Job Insecurity and Precarious Work leading to Short-termism: Financialization encourages short-term profit maximization, which can lead to companies cutting jobs, reducing benefits, or using contract labor to avoid long-term commitments. This instability undermines the dignity of employment as workers can't rely on consistent, dignified work.

Erosion of Work Ethic and Community Disconnect: As financial motives drive corporate behavior, there's less emphasis on community investment or the long-term health of local economies. This can lead to a decline in community-based work where individuals took pride in contributing to their local environment.

Psychological Impact: When one's work is no longer seen as a source of personal or communal value but merely as a cost in a financial strategy, it impacts self-esteem and the sense of purpose derived from work. The narrative that success is measured by financial wealth rather than by the quality or integrity of one's work further diminishes the dignity of honest labor.

In summary, the financialization of everything has created an economic environment where the dollar's purchasing power can be eroded by speculative practices, and where the traditional forms of work that once provided both income and dignity are devalued or destabilized. This has led to a broader societal shift where the intrinsic value of honest, productive work is overshadowed by the pursuit of financial gains, often at the expense of the common individual's well-being and respect.

Case Study: Corporate Giants

Big Pharma

The pharmaceutical industry is often criticized for its profit-driven practices. One key issue is drug pricing, where medications can be priced beyond the reach of many people, even in developed countries. This practice can be exacerbated by patent manipulation, where companies extend patent life through minor modifications to existing drugs or by patenting multiple aspects of a drug. This not only maintains high prices but also delays generic alternatives, which could offer more affordable options. Moreover, the focus of research and development tends to be skewed towards diseases prevalent in wealthier markets or those that promise high financial returns, potentially neglecting global health priorities like diseases in poorer regions or less commercially viable conditions.

This profit-first approach can undermine the fundamental mission of healthcare which should ideally prioritize health outcomes over financial gain. It raises ethical questions about access to essential medicines and the role of corporate entities in public health.

Tech Giants

Tech companies have transformed global connectivity and information access, but this comes with its set of challenges. Layoffs, often seen as a means to streamline operations or boost stock prices, can have a significant human cost, impacting not just the employees but also local economies where these companies operate.

Data monetization is another contentious area where user data is leveraged for advertising or sold to third parties, often with little transparency or control given back to users. This can lead to a degradation of privacy and a sense among users that they are merely products in a digital marketplace. Additionally, the prioritization of ad revenue over user privacy or well-being can manifest in the design of platforms that might encourage engagement through addictive mechanisms or by showing content that is sensational rather than informative or beneficial.

These practices highlight a tension between technological advancement and ethical responsibility, questioning how much companies should prioritize profit versus the welfare and rights of their users and employees.

Case Study: Financial Sector

Investment Banks

High-frequency trading exemplifies how technology can be used to gain an edge in financial markets, often at the expense of market fairness. This practice allows for the buying and selling of securities at speeds and volumes that can outpace other market participants, potentially destabilizing markets or creating conditions ripe for manipulation.

The creation of complex financial products like derivatives can be lucrative for those who understand them but can also lead to significant risks for the broader economy, as seen in events like the 2008 financial crisis. Here, the drive for profit might overshadow the need for financial stability and ethical investment practices.

Private Equity

Private equity firms sometimes engage in what's known as "strip and flip" tactics, where they acquire companies, restructure them heavily (often involving significant debt and job cuts), and then sell them off for profit. While this can lead to short-term gains for investors, it can also result in long-term damage to the company's sustainability, employee livelihood, and community stability.

This approach often reveals a stark contrast between financial gain and social responsibility, illustrating how decisions made in boardrooms can have far-reaching impacts on the ground, affecting everything from local job markets to national economic health.

Both sections underline a recurring theme in modern capitalism where the drive for profit can sometimes override considerations of social welfare, ethical business practices, or long-term societal benefits. They encourage a debate on how businesses can balance profitability with responsibility.

Impact on Workers and Communities

The Human Cost

Job Insecurity and Psychological Impact: The trend towards financialization in corporate strategies often leads to an environment where job security is significantly undermined. Employees might experience frequent restructurings, mergers, or acquisitions where their roles are re-evaluated or eliminated for cost-cutting or efficiency measures. This can foster a pervasive sense of insecurity, leading to chronic stress, anxiety, and a sense of powerlessness over one's career path. The psychological toll includes burnout, depression, and a decline in mental health, as the fear of job loss becomes a constant background noise in many workers' lives.

Moreover, the focus on financial metrics over human elements can lead to reduced job satisfaction. When employees are seen merely as costs to be minimized rather than assets, their morale and engagement suffer. The devaluation of non-financial contributions, such as loyalty, community service, or long-term expertise, can make workers feel underappreciated and lead to a disconnection from their work, reducing productivity and innovation.

Community Impact and Social Repercussions

Economic Dislocation: When companies prioritize profit maximization, they might relocate operations to areas with cheaper labor or better tax incentives, leaving communities behind with high unemployment rates, reduced local tax revenues, and a diminished economic base. This can lead to the decline of local businesses that once thrived on the spending power of workers employed by these corporations.

Neglect of Social Responsibilities: Corporations often cut back on community engagement, mental health support, or equitable wage policies which are crucial for fostering a supportive societal fabric. Without these supports, communities can struggle with higher levels of poverty, crime, and social unrest. The lack of investment in mental health or equitable wages can exacerbate social divides, creating environments where the gap between the rich and poor widens, leading to resentment and social fragmentation.

Environmental Degradation: Profit-driven decisions can sideline environmental considerations, leading to pollution, resource depletion, or climate change impacts that directly affect community health and sustainability. The degradation of local environments not only affects physical health but also diminishes the quality of life, making areas less livable or attractive for future generations.

Loss of Community Identity: As companies move or change hands, there's often a loss of local identity or corporate culture that was once tied to these businesses. This can erode the sense of community pride and belonging, impacting local culture and heritage.

Long-term Societal Effects: The overarching impact is a society where the value of human dignity, community cohesion, and environmental stewardship might be overshadowed by short-term financial gains. Over time, this can lead to a less resilient society, more prone to economic shocks, social inequalities, and public health crises. The shift towards financialization, if unchecked, might foster a culture where the fundamental needs of people and communities are not aligned with the goals of the corporations that operate within them.

This section highlights the need for a balanced approach in corporate governance, where financial success is not the sole metric of achievement but is weighed alongside social responsibility, worker well-being, and community health. It calls for policies and corporate cultures that recognize the intrinsic value of human elements in business and strive for sustainable practices that benefit both profit and people.

Money and Relationship Dynamics

Personal Relationships and the Time Deficit

The relentless pursuit of financial success often means individuals allocate more time to work, sometimes at the expense of personal relationships. This can lead to a scenario where partners, family members, and friends receive less of the time, attention, and emotional investment necessary for nurturing deep, meaningful connections. The result can be superficial interactions, where conversations are brief, rushed, and devoid of the depth needed to maintain strong bonds. Over time, this can lead to feelings of neglect or loneliness, as personal relationships require time and presence to flourish.

The pressure to succeed financially can also create stress and fatigue, reducing the emotional energy available for love, empathy, and support within relationships. This might manifest in less patience, understanding, or willingness to engage in the give-and-take that healthy relationships require.

Trust and Institutional Integrity

On a broader societal level, when financial incentives appear to be the primary driver behind decisions made by institutions—be it in government, healthcare, education, or business—the public's trust in these entities can erode. When people perceive that actions are motivated by profit rather than the public good or ethical considerations, cynicism about human motives grows. This cynicism can extend from distrust in corporate practices (like pharmaceutical pricing or data privacy violations) to skepticism about governmental policies or judicial fairness if they're seen as serving financial interests over justice or welfare.

Examples in Society

Government: When policy-making or regulation seems influenced more by lobbying from big businesses than by public interest, trust in government decreases. This can lead to lower civic engagement, voting rates, or even support for populist movements that promise to dismantle perceived corrupt systems.

Corporations: Instances of corporate scandals, where profit trumps ethics, like environmental disasters, financial frauds, or labor abuses, further erode trust. Consumers might become more skeptical of brand promises or corporate social responsibility claims.

Media and Information: In an era where media can be heavily influenced by financial backers, trust in news and information sources diminishes, leading to phenomena like "fake news" and a fragmented media landscape where truth becomes contested.

The Diminishing of Love and Trust

Love, in its various forms, thrives on trust, mutual respect, and genuine communication. When these elements are compromised by an overarching focus on financial gain, the quality of relationships suffer. Trust becomes a casualty as people start questioning the sincerity behind actions, whether in personal interactions or in dealings with institutions.

This erosion can lead to a society where relationships are more transactional, where cynicism and skepticism are normalized, and where the concept of community and collective well-being is overshadowed by individual or corporate ambition. The result might be a more isolated society, where the bonds that once held communities together weaken, and where love and loyalty are seen more as commodities than as intrinsic values.

Cultural and Psychological Impact

Culturally, this shift can influence art, literature, and media towards narratives of distrust, betrayal, or the critique of systems. Psychologically, individuals might grow up with a worldview where self-interest is the assumed norm, potentially leading to more guarded personal interactions or a reluctance to commit deeply to others or to societal causes.

This section underscores the need for a cultural and systemic reevaluation of what we value, promoting environments where love, trust, and genuine human connection are not just by-products but are central to our collective goals and institutional behaviors.

Alternatives and Resistance

B Corporations

B Corporations (or Benefit Corporations) represent a significant shift in how businesses can operate. Certified by B Lab, these companies are legally bound to consider the impact of their decisions on not only shareholders but also workers, the community, and the environment. This legal framework allows them to balance profit with purpose, ensuring that their business practices align with broader social and environmental goals. B Corps often engage in practices like fair labor policies, sustainable sourcing, and community investment. By measuring success through a triple bottom line of people, planet, and profit, they provide an alternative business model where financial success is not at odds with social responsibility.

Cooperatives

Cooperatives are organizations owned and democratically controlled by their members, who might be employees, consumers, or producers. This structure inherently prioritizes community and collective well-being over singular profit motives:

- Worker Cooperatives empower employees with ownership and decision-making power, often leading to more equitable distribution of profits, higher job satisfaction, and less income inequality within the organization.

- Consumer and Producer Co-ops focus on meeting the needs of their members while ensuring ethical production or consumption practices, which can lead to sustainable business practices and stronger community ties.

- Cooperatives tend to be more resilient during economic downturns due to their focus on community needs rather than speculative gains. They foster a culture where business decisions are made with a long-term view of community health rather than short-term profit.

Social Enterprises

Social enterprises are businesses that apply commercial strategies to achieve social, cultural, or environmental goals. They operate with the dual aim of generating profit while simultaneously addressing social issues:

- These entities might focus on employing marginalized groups, providing affordable services in underserved areas, or combating environmental degradation.

- They often reinvest a significant portion of their profits back into their mission, rather than distributing all earnings to shareholders.

- Social enterprises can act as catalysts for change, demonstrating that business can be a force for good. They challenge the conventional business wisdom by showing that profitability and social impact can coexist, offering scalable solutions to some of society's most pressing problems.

Movements and Advocacy

Beyond specific business models, there are broader movements advocating for systemic change:

- Ethical Investment - Encouraging investments in companies that adhere to ethical, social, and environmental standards.

- Corporate Accountability - Campaigns and advocacy groups that push for transparency, fair labor practices, and environmental stewardship in corporate operations.

- Localism - Efforts to support local economies, reducing the dominance of large, often profit-focused corporations, and fostering community resilience.

Cultural Shift

These alternatives contribute to a cultural shift where success is redefined. There's a growing recognition among consumers, employees, and investors that businesses should contribute positively to society and the environment. This is evidenced by:

- Increased consumer demand for ethically produced goods.

- A workforce that values purpose over just paychecks.

- Investors looking into ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) criteria when making investment decisions.

Challenges and Opportunities: While these alternatives face challenges in scaling or competing with traditional profit-driven models, they also present opportunities for innovation in business practices, governance, and economic theory. They illustrate that there are viable paths where the economy can serve human and planetary well-being, creating a more inclusive and sustainable future.

This section highlights the importance of systemic change and grassroots movements in redefining how we view and conduct business, advocating for a world where economic activities are aligned with ethical, social, and ecological responsibilities.

The Path Foward: Reimagining the Economy

Stakeholder Capitalism

This model suggests a shift from shareholder primacy to stakeholder inclusivity. Here, companies would be obligated to consider the interests of all stakeholders—employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and the environment—alongside shareholders. This could involve changes in corporate governance, where boards are required to account for broader impacts in their decision-making processes. Companies might redefine their mission statements to explicitly include commitments to social and environmental goals.

By valuing all stakeholders, businesses could foster environments where workers feel more valued, communities benefit from corporate activities, and environmental sustainability becomes a core business strategy. This could lead to more resilient economies, where wealth is distributed more equitably and business practices contribute positively to society.

Universal Basic Income (UBI)

UBI proposes giving all citizens a regular, unconditional sum of money, regardless of employment status. The idea is to provide a financial safety net that:

- Reduces Financial Stress which can allow individuals to pursue education, start businesses, or engage in creative endeavors without the constant pressure of financial survival.

- Meets basic needs so people may allocate more time to family, friends, and community, potentially leading to stronger social bonds and a society where love and care are prioritized.

- Encourages Work-Life Balance by alleviating the necessity to work multiple jobs or overtime, UBI could promote better health, well-being, and life satisfaction.

Implementing UBI would require significant policy innovation, funding mechanisms, and careful consideration of economic impacts like inflation or work incentives. This also undermines the importance of education at an early age which can give the knowledge and tools needed to build and provide innovative goods and services for consumers without the need of a subsidy.

Regulatory Reforms

To curb the excesses of financial speculation and ensure economic activities enhance human life, stronger regulations could be:

- Financial Market Oversight: Tightening rules around speculative practices like high-frequency trading, or imposing taxes on short-term capital gains to discourage quick profit-taking at the expense of market stability.

- Corporate Accountability: Enhanced transparency requirements, stricter environmental regulations, and labor laws that ensure fair wages and conditions, reducing the human cost of corporate profit-seeking.

- Anti-Monopoly Laws: Vigorous enforcement to prevent the concentration of market power which can lead to practices like predatory pricing or the stifling of innovation.

These reforms aim to create a market where competition is fair, innovation is encouraged, and the economy serves broader societal goals. They could prevent financial bubbles, protect consumers and workers, and ensure that economic growth translates into widespread benefits.

Cultural and Educational Changes

Beyond policy, reimagining the economy involves cultural shifts where:

- Education Systems teach not just financial literacy but also ethical, environmental, and social responsibility.

- Media and Public Discourse normalize discussions around economic models that prioritize human well-being over GDP growth alone.

- Community Engagement is encouraged to foster local economies that are resilient and reflective of community values rather than global profit motives.

Technology and Innovation

Leveraging technology to solve social problems rather than just to maximize profit. For instance:

- Developing technologies that reduce environmental impact or improve access to education and healthcare.

- Encouraging innovations in cooperative or community-based economic models through tech platforms.

Global Cooperation

- Recognizing that many of these changes require international cooperation, particularly in areas like climate change, labor rights, and tax evasion. Countries could work together to set standards and share best practices for a more equitable global economy.

-

This path forward requires not just policy changes but a collective rethinking of what we value in our economic systems, aiming for an economy that nurtures human potential, fosters community, and respects our planet's limits.

Conclusion

The modern economy's focus on financialization has not only shifted societal priorities but has also contributed to an erosion of love by fostering an environment where financial metrics often eclipse human connections. This chapter has demonstrated how this shift affects individuals, communities, and the broader societal fabric. It calls for a reflection on how we can reclaim an economic system where love and human relationships are not just byproducts but fundamental goals. The path forward involves both personal commitments to value relationships and systemic changes that ensure the economy serves human needs, promoting a world where love can flourish once again.