Gains and losses

In contemporary society, money is often seen as the key to freedom, security, and success. Yet, this chapter argues that financial wealth doesn't equate to true freedom. Money offers an illusion of autonomy but binds us with societal pressures, stress, and disconnection from what matters, like time with loved ones, which impacts community and mental health.

Inflation is a hidden cost of money, reducing its purchasing power and serving as a tax on savings. As governments print more money, inflation rises, making each dollar worth less. This inflation acts as the carrot on the stick, encouraging spending over saving due to money's decreasing value, driving economic activity but also promoting a chase for more, often at the cost of community and environmental well-being.

We should advocate for a cultural shift where money is merely a tool, not the goal. By reevaluating our relationship with money, we can prioritize love, community, and growth over financial accumulation, aiming for a life where money supports our journey, not dictates it. This vision leads to healthier communities, better mental health, and a sustainable future, recognizing inflation as a reminder to balance life beyond economic measures.

The Psychological Burden of Financial Security

Money as a Stressor

The constant chase for financial security is linked to increased rates of anxiety, depression, and burnout. Psychological research demonstrates how financial concerns can overshadow life's other aspects, leading to a scenario where money becomes the yardstick for self-worth and security. This can create a cycle of stress where individuals measure their life's success by their bank balance rather than their happiness or relationships.

Financial Stress and Mental Health

Anxiety and Depression: Numerous studies have established a direct link between financial stress and mental health issues like anxiety and depression. The fear of not having enough money for basic needs, unexpected expenses, or future security can lead to chronic worry, which in turn can escalate into clinical anxiety or depressive disorders.

Burnout: The pressure to maintain or increase one's financial standing can lead to overworking, which is a primary contributor to burnout. Burnout is characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism about one's job, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment, all of which can severely impact mental health.

Money as a Measure of Self-Worth

Societal Pressures: In many societies, financial success is equated with personal success. This cultural narrative can make individuals feel their value is tied to their wealth, leading to a self-esteem that fluctuates with financial status.

Identity and Fulfillment: When money becomes the primary measure of success, personal fulfillment might be neglected. People might pursue careers or lifestyles not out of passion or interest but for financial gain, leading to a life that feels hollow or unfulfilling despite outward signs of success.

The Cycle of Stress

Constant Comparison: Social media and the culture of comparison exacerbate financial stress. Seeing others' curated lives of apparent wealth can create envy or a sense of inadequacy, pushing one to work harder or spend beyond one's means to keep up appearances.

Debt and Financial Instability: The pursuit of security might lead to living beyond one's means, accruing debt, which then becomes a source of continuous stress. Debt can feel like a trap, with each payment cycle reinforcing feelings of failure or lack of control over one's life.

Future Uncertainty: Concerns about retirement, healthcare costs, or economic downturns can keep individuals in a state of perpetual planning and worry, detracting from enjoying the present.

Psychological and Behavioral Impacts

Risk Aversion or Risk-Taking: Paradoxically, financial insecurity might make some individuals either overly cautious, avoiding any financial risk, or recklessly speculative, hoping for a big payoff to solve their problems.

Relationship Strain: Money issues are a top cause of conflict in relationships. Disputes over spending, saving, or financial priorities can erode partnerships, leading to stress not just for the individual but within family dynamics.

Breaking the Cycle

Mindfulness and Financial Education: Learning to manage finances better through education and mindfulness can alleviate some stress. Understanding one's financial situation, setting realistic goals, and learning to live within one's means can foster a healthier relationship with money.

Redefining Success: Personal development often involves redefining what success means to oneself, perhaps valuing time, relationships, or personal growth over purely financial achievements.

Therapeutic Interventions: Therapy can be instrumental in dealing with the psychological impacts of financial stress, helping individuals to address underlying issues related to self-worth, anxiety, or depression.

Community and Policy Support: Enhanced social safety nets, better access to affordable healthcare, and policies that encourage work-life balance can mitigate some of the financial pressures individuals face, reducing the psychological burden.

In summary, while financial security is necessary, its pursuit can have profound psychological costs if not balanced with other aspects of well-being. Recognizing money's role as both a necessary tool and a potential stressor can lead to more holistic approaches to living a fulfilled life.

The Carrot on a Stick - Inflation as a Cost of Money

Inflation, in its simplest form, is the rate at which the general level of prices for goods and services is rising, which invariably leads to a decrease in the purchasing power of money. This phenomenon acts as a hidden tax on money, eroding its value over time. When inflation rises, each dollar in your pocket or bank account buys less than it did before. This loss of purchasing power is a direct cost associated with holding money.

The mechanics of inflation are complex, but at its core, it's often the result of an increase in the money supply that outpaces economic growth. Governments and central banks might increase the money supply to stimulate the economy, fund welfare programs, or manage debts, but this can lead to an excess of money chasing too few goods, thereby driving prices up. For individuals, this means that saving money becomes less attractive as the real value of their savings diminishes. Instead, there's a push towards spending or investing in assets that might outpace inflation, such as real estate or stocks, which in itself can fuel further inflation through increased demand.

Inflation as the Carrot on the Stick

Inflation serves as a motivational force, akin to the proverbial carrot on the stick. It incentivizes spending and discourages saving because the value of money decreases over time. This economic behavior ensures that money kept under the mattress or in low-yield accounts loses value, pushing consumers and businesses to spend or invest.

From a policy perspective, inflation can be used strategically. Low, controlled inflation is often seen as a sign of a healthy, growing economy where demand is robust. It encourages spending which in turn can stimulate economic activity, create jobs, and foster growth. However, this carrot has a dual edge; while it motivates current spending, it can also lead to a cycle where people demand higher wages to counteract the rising costs, leading to a wage-price spiral if not managed properly.

Moreover, inflation can be a tool for governments to reduce the real value of debt. By allowing inflation to rise, the burden of fixed debt payments in nominal terms becomes lighter over time in real terms, essentially diminishing the debt's real value. This can be seen as a carrot for governments who might otherwise face unsustainable debt levels. However, for the citizens, this translates into a stick as their savings and fixed incomes lose purchasing power.

The Societal Impact

The implications of inflation extend beyond economics into societal structures. It affects how people plan for the future, from retirement savings to investments in education. For those on fixed incomes or with savings in cash, inflation can be particularly punitive, acting more like a stick than a carrot. It forces a continuous chase for income or investment returns that outstrip inflation rates, often at the cost of immediate well-being or community involvement.

Furthermore, inflation can exacerbate income inequality. Those with assets that appreciate in value during inflationary periods, like property or stocks, benefit, while those relying solely on wages or fixed incomes find their standard of living eroded. This dynamic can lead to social tensions, as the disparity between the rich, who can leverage inflation, and the poor, who are its victims, widens.

Inflation, therefore, is both a cost of money and an economic mechanism that acts as the carrot on the stick. It drives consumer behavior, influences government policy, and shapes the socio-economic landscape. While moderate inflation can be a sign of economic vitality, unchecked inflation can lead to significant societal disruptions. Understanding and managing inflation is crucial for policymakers to ensure it serves as a carrot for economic growth without becoming a stick that undermines public trust and economic stability. The challenge lies in balancing this carrot and stick to foster an environment where money serves as a facilitator of prosperity, not a source of perpetual chase or loss.

The Illusion of Freedom

Financial Chains: While money is often celebrated as a tool for freedom, it paradoxically can bind individuals to a life of work they might not enjoy. The need to earn enough not just to survive but to thrive in societal terms leads many to forgo personal passions or hobbies, which are essential for a fulfilling life. This section critiques the notion that financial wealth equates to personal freedom.

The Paradox of Financial Freedom

Economic Necessity vs. Personal Fulfillment: While money provides the means for basic needs and comforts, the quest for more can trap individuals in careers or lifestyles they don't enjoy. The irony is that many work long hours in jobs they dislike to afford a lifestyle that promises freedom but at the cost of personal liberty in terms of time, creativity, and passion.

The Rat Race: This term encapsulates the endless cycle of working to earn more, only to spend more, which necessitates even more work. This cycle can feel like running in place, where the goal of financial freedom is perpetually just out of reach, leading to a life where one is always working towards the next financial milestone rather than living in the present.

Societal Expectations and Lifestyle Inflation

Keeping Up with the Joneses: Social pressures to maintain or elevate one's status through material possessions or experiences can lead to lifestyle inflation. Individuals might find themselves in a situation where their expenses grow with their income, thus requiring continuous work to sustain this elevated lifestyle rather than achieving actual freedom.

Perceived Success: Society often equates success with wealth, leading people to chase after financial markers of success rather than personal satisfaction or happiness. This can result in a life where one's achievements are measured by external validations like houses, cars, or vacations, rather than internal fulfillment.

The Cost of Time

Time as Currency: There's a finite amount of time in one's life, and the more of it that's spent earning money, the less is available for personal growth, relationships, or leisure. Even with high earnings, if most of one's life is dedicated to work, the freedom to enjoy those earnings is severely limited.

Opportunity Cost: Choosing a high-paying job over one that might offer more personal satisfaction or less stress can mean missing out on life experiences, personal development, or time with loved ones. This trade-off often isn't fully considered when pursuing financial gain.

While money is often heralded as the key to freedom, it can paradoxically chain individuals to lives dominated by work they may not enjoy. The pursuit of financial wealth to meet societal expectations or to achieve a certain lifestyle can lead to a cycle of endless work, where the true essence of personal freedom—time for passions, relationships, and personal fulfillment—is sacrificed. This critique highlights how the conventional chase for financial success might not equate to personal liberty, as it often entails trading away life's most valuable currency, time, for the illusion of freedom.

Money and Love

The Commodification of Affection

Money influences the very fabric of personal relationships. From dating, where financial status can dictate partner selection, to family dynamics where the provider role is glorified, money often dictates emotional bonds. Phenomena like "gold digging" or the societal pressure to equate love with material provision show how love can be commodified, potentially diminishing the authenticity of relationships.

Influence on Partner Selection

Dating and Financial Status: In the dating scene, one's financial status can be a deciding factor in partner selection. This isn't universally true, but there's undeniable pressure where wealth is often seen as a sign of stability, success, or even desirability. This can lead to relationships where financial compatibility is prioritized over emotional connection.

Economic Filters: Dating apps and social circles often act as economic filters, where individuals are more likely to encounter and connect with others from similar economic backgrounds, potentially limiting emotional connections based on socioeconomic status.

Family Dynamics and the Provider Role

Traditional Expectations: In many cultures, there's an expectation for one partner (often traditionally the male) to be the primary breadwinner. This can skew family dynamics, where love might be expressed through financial provision, and failure to meet these expectations can lead to tension or even relationship breakdown.

Economic Dependency: When one partner is significantly more financially dependent on the other, it can alter the power dynamics within the relationship, potentially leading to a transactional view of love where affection is tied to financial support.

The Commodification of Love

Gold Digging and Opportunism: The term "gold digger" reflects a societal acknowledgment of relationships where one party is primarily interested in the other's wealth. While not all relationships with financial disparity are opportunistic, the stereotype exists and influences how people perceive and judge relationships.

Material Expressions of Love: Love is often shown through gifts, experiences, or financial support. While these can be genuine expressions of affection, there's a risk of equating love with money, where the quality or quantity of gifts becomes a measure of love's depth or sincerity.

Marriage and Financial Considerations: Marriages are sometimes entered or maintained with significant financial considerations in mind, from prenuptial agreements to staying in unfulfilling relationships for financial security.

Societal and Cultural Pressures

Media and Popular Culture: Movies, TV shows, and social media often glorify lifestyles associated with wealth, subtly or overtly suggesting that money can buy love or happiness. This narrative can pressure individuals to pursue or value partners based on their financial standing.

Social Status: In many societies, the financial status of individuals or families can elevate or diminish social standing, which in turn influences how relationships are formed or perceived.

Potential Diminishment of Authenticity

Transactional Relationships: When relationships are influenced by financial motives, they risk becoming transactional. The authenticity of love can be questioned if one's motives are seen as financially driven rather than emotionally based.

Pressure on Relationships: The pressure to provide financially can strain relationships, where one or both partners might feel unfulfilled or resentful if financial expectations aren't met.

Navigating the Money-Love Nexus

Open Communication: Discussing financial expectations, values, and roles openly can prevent misunderstandings and foster a relationship based on mutual respect rather than financial dependency.

Shared Values: Couples who prioritize shared values over financial status might build stronger, more authentic bonds, focusing on emotional and personal growth together.

Redefining Love: There's a growing cultural shift towards recognizing love as something beyond financial provision, valuing emotional support, intellectual companionship, and shared life goals.

Education on Financial Independence: Promoting financial literacy and independence for all individuals can reduce the commodification of love by ensuring that relationships aren't based solely on economic necessity.

While money undeniably plays a role in how relationships are formed and maintained, the challenge lies in not letting it overshadow the genuine emotional connections that form the true basis of love. Recognizing and navigating these dynamics can lead to healthier, more authentic relational experiences.

The Impact on Community and Society

Social Fragmentation

When individual financial gain becomes the priority, community bonds weaken. The focus on personal wealth accumulation can lead to a society where competition overshadows cooperation, and communal activities diminish. Economic disparities within communities exacerbate this, leading to social isolation, where neighbors are more competitors than friends.

Erosion of Community Bonds

Individualism Over Collectivism: In societies where personal financial success is highly valued, there's often a shift towards individualism, where personal achievement is prized over community welfare. This can diminish communal activities like local festivals, volunteer work, or simple neighborhood interactions, as individuals are less inclined to invest time in unpaid community engagement when their focus is on economic advancement.

Loss of Social Capital

Communities thrive on social capital: the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively. When individuals prioritize personal wealth, these networks weaken, reducing trust, reciprocity, and mutual aid, which are essential for a supportive community environment.

Competition Over Cooperation

The dynamics between competition and cooperation shape not only markets but also social interactions within communities. Here’s an elaboration on how economic competition can overshadow cooperation:

Economic Competition: In an environment where everyone is seen as a competitor for resources, jobs, or status, cooperation can take a backseat. This competitive atmosphere can lead to less willingness to collaborate on community projects or support neighbors in need, fostering a 'me first' attitude.

- Resource Scarcity Perception: In environments where resources (like job opportunities, housing, or educational slots) are perceived as limited, individuals might see each other primarily as competitors rather than potential collaborators. This scarcity mindset can lead to a survival-of-the-fittest attitude where personal gain is prioritized over communal well-being.

- Career and Status: In many professional settings, advancement often comes at the expense of others; promotions, bonuses, or recognition might be zero-sum, where one person's rise can mean another's stagnation or fall. This competitive environment can discourage sharing knowledge or helping colleagues, as doing so might be seen as strengthening a competitor.

- Impact on Community Engagement: When individuals are focused on outdoing one another for economic advantages, community initiatives that require collective effort often suffer. People might be less inclined to volunteer time or resources for community projects if these activities are perceived as not directly contributing to their economic or career status.

- Fostering a 'Me First' Attitude: This competitive culture can cultivate a mindset where personal success is the ultimate goal, often at the expense of others. The idea that to get ahead, one must look out for oneself first can diminish altruistic behaviors, leading to a less cohesive society where empathy and mutual support are undervalued.

Zero-Sum Thinking: The belief that one person's gain must come at another's expense can permeate social interactions, where helping others is seen as potentially detrimental to one's own financial or social standing.

- Fundamental Belief: Zero-sum thinking operates on the premise that there's only so much wealth, power, or recognition to go around. Therefore, any gain by one individual or group is believed to directly equate to a loss for another. This belief can infiltrate everyday social interactions, making people wary of cooperative actions because they might see them as self-sacrificing.

- Impact on Social Interactions: In social settings, if helping someone is perceived as giving away an advantage or resource, individuals might be less likely to extend help. For example, sharing job leads, business opportunities, or even simple advice might be withheld if one believes it could reduce their own standing or opportunities.

- Barriers to Collaboration: In business or community settings, zero-sum thinking can lead to reluctance in forming partnerships or alliances. The fear that a partner might gain more from the collaboration than oneself can stifle potential collaborations that could benefit all parties involved.

- Psychological and Social Effects:

- Distrust: This mindset breeds distrust, as individuals might constantly be on guard against being "taken advantage of" or "losing out."

- Reduced Innovation: In a truly competitive, zero-sum scenario, sharing ideas or innovations might be minimized for fear that others will capitalize on them, which can slow down collective progress or innovation

- Social Isolation: Over time, this kind of thinking can lead to social isolation, as people might withdraw from communal activities or shy away from forming deep connections due to perceived competitive threats.

Mitigating the Effects:

-

Promoting a Win-Win Mentality: Education and cultural narratives can shift to highlight scenarios where cooperation leads to mutual benefits, showing that success isn't necessarily at the cost of others.

-

Policy and Economic Structures: Designing economic policies or business models that encourage collaboration rather than just competition can help. This might include incentives for teamwork, shared resource models, or community-based economic initiatives.

-

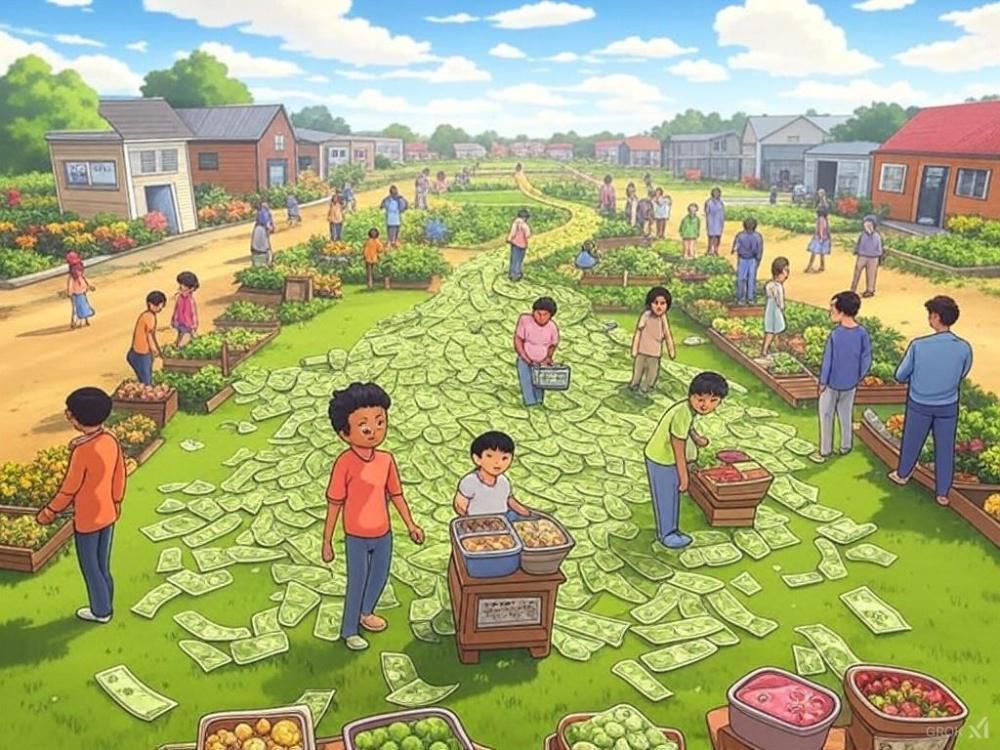

Community Building: Programs that emphasize communal benefits, like local co-ops, mutual aid networks, or community gardening, can remind people of the value of cooperation.

-

Leadership and Role Models: Leaders in business, politics, or community roles can set examples by demonstrating how cooperation can lead to success, perhaps through public-private partnerships, corporate social responsibility, or community leadership.

-

Encouraging Empathy: Fostering environments where empathy is valued can combat zero-sum thinking by emphasizing the human aspect of success and failure, encouraging people to see beyond immediate competition.

While competition can drive innovation and efficiency, an overemphasis on it at the expense of cooperation can lead to a fragmented society where individual success is celebrated over collective well-being. Balancing these forces is key to nurturing communities that thrive on both individual achievement and collective progress.

Economic Disparities and Social Isolation

Widening Gaps: Economic inequality can lead to social stratification where different economic classes live in separate worlds, even within the same neighborhood. This can manifest in physical separation (gated communities vs. public housing) or in social separation (different schools, clubs, or social circles), further isolating individuals from diverse community experiences.

Isolation and Mistrust: As economic disparities grow, so can mistrust between different socioeconomic groups. Those with less might view wealthier neighbors with suspicion or envy, while the affluent might isolate themselves to avoid perceived threats or to keep up their social standing, leading to a lack of interaction and understanding across economic lines.

Impact on Community Health

Decreased Civic Engagement: With less community interaction, civic engagement drops. People are less likely to vote, attend town meetings, or participate in local governance, which can lead to a less responsive or representative local government.

Mental Health and Well-being: The social isolation and competitive atmosphere can contribute to increased stress, anxiety, and loneliness, negatively impacting mental health. The sense of belonging, which is crucial for psychological well-being, diminishes.

Cultural and Social Loss

Loss of Traditions: As people become more focused on personal economic pursuits, traditional community events or cultural practices that require collective effort or time might fade away, leading to a loss of cultural identity and heritage.

Decline in Social Support Systems: With less communal interaction, informal support systems like neighbors helping neighbors in times of need weaken, putting more strain on formal systems (like welfare or emergency services) or leaving individuals without support.

Reimagining Community

Redefining Success: Encouraging societal values that celebrate community contributions alongside personal achievements might help. Recognizing and rewarding community service or cooperative endeavors can foster a culture where community well-being is seen as part of personal success.

Economic Policies for Equity: Policies aimed at reducing economic inequality, such as progressive taxation, affordable housing, and universal basic services, could help mitigate some of these effects by fostering a sense of shared destiny.

Initiatives for Community Building: Programs that bring people together, whether through shared spaces, community gardens, local markets, or cultural events, can rebuild those bonds, promoting a community-first mindset.

While individual financial gain is not inherently negative, when it becomes the overriding priority, it can lead to a loss of community vitality, reducing the quality of life for everyone involved. Balancing personal ambition with community engagement is vital for a healthy, cohesive society.

Generational Impact

Passing Down the Burden

Attitudes towards money and the necessity of work are often passed down through generations, perpetuating a cycle where financial success is prized over relational richness. This section examines how different generations view work, money, and life quality, showing a trend where each successive generation feels more pressure to achieve financial success at the potential cost of personal happiness.

Transmission of Values

Cultural Inheritance: From a young age, individuals learn about work ethic, the value of money, and the importance of financial security from their parents or guardians. These lessons can become deeply ingrained, shaping one’s life choices, career paths, and even personal relationships.

Modeling Behavior: Children observe whether their parents prioritize work over family time or if financial discussions dominate over those about happiness or personal development. This modeling can lead to a normalization where financial success is seen as the primary goal.

Generational Perspectives on Work and Money

The Silent Generation and Baby Boomers: Often characterized by a strong work ethic, these generations might have seen work as a duty and financial security as the ultimate goal, especially in the context of post-war economic booms or the need to recover from economic downturns. They might have instilled in their children the belief that hard work equals success, with less emphasis on work-life balance.

Generation X: Growing up with dual-income households becoming the norm and experiencing economic instability (like the 1980s recession or the dot-com bubble burst), Gen X might have learned to balance work with family but still emphasized financial independence and security.

Millennials: Facing economic challenges like the 2008 financial crisis, student debt, and a highly competitive job market, Millennials often prioritize work-life balance more than previous generations but still feel immense pressure to achieve financial stability, often at the expense of personal satisfaction or relational depth.

Generation Z: Entering adulthood amidst global economic shifts, technological revolutions, and climate concerns, Gen Z seems to value flexibility, purpose in work, and mental health more than pure financial gain. However, they are not immune to the pressure of securing financial success, especially given the rising costs of living and job market uncertainties.

The Pressure to Succeed Financially

Increasing Barriers: Each generation faces new or intensified barriers to financial success, from housing affordability to the gig economy's instability. This often leads to a sense that they must work harder than previous generations to achieve similar or lesser results.

Parental Aspirations: Parents, having experienced their own financial struggles or successes, might project their aspirations or fears onto their children, sometimes pushing them towards high-paying careers over what might make them happier.

Loss of Community Identity: As companies move or change hands, there's often a loss of local identity or corporate culture that was once tied to these businesses. This can erode the sense of community and belonging, impacting local culture and heritage.

Impact on Personal Happiness

Work Over Well-being: The belief that one must achieve a certain level of financial success to be considered successful can lead to delayed life milestones (like marriage or having children) or engaging in work that doesn't fulfill on a personal level.

Relational Strains: The focus on financial success can mean less time for nurturing relationships or engaging in community activities, leading to a life where professional achievements are celebrated more than personal or relational ones.

Breaking the Cycle:

- Conscious Parenting: Parents can consciously choose to emphasize values like creativity, relationships, and personal fulfillment alongside financial responsibility, showing that success is multi-dimensional.

- Education on Life Balance: Educational systems and societal messages could shift to teach not just financial literacy but also life balance, psychological well-being, and the importance of passion-driven careers.

- Intergenerational Dialogue: Encouraging conversations between generations about what truly constitutes a good life might help in redefining success. Older generations can share lessons learned, while younger ones can introduce new perspectives on work and life integration.

- Cultural Shifts: As society evolves, there's a budding movement towards valuing mental health, sustainability, and community over pure economic gain, which could influence generational attitudes if fostered broadly.

In summary, while each generation inherits a set of values around work and money, there's also an opportunity for each to redefine these values. The challenge lies in fostering environments where financial security is balanced with personal happiness and relational richness, potentially breaking the cycle of equating personal worth solely with financial success.

Reassessing Value

A Balanced Life

There's a call for reevaluating what we truly value in life. Movements like minimalism, financial independence, retire early (FIRE), or communal living challenge the traditional money-centric lifestyle. These philosophies advocate for a life where financial resources are tools for living well, not the primary goal, promoting a culture where time, relationships, and personal well-being are valued over financial metrics.

Emerging Philosophies

Minimalism: This lifestyle philosophy encourages individuals to live with less, focusing on what's essential. It's not merely about decluttering spaces but decluttering life from the pressures of consumerism, which often equates to working more to buy more. Minimalism promotes the idea that less can be more, where simplicity leads to greater life satisfaction and less stress.

Financial Independence, Retire Early (FIRE): The FIRE movement emphasizes achieving financial independence as soon as possible to retire early or at least have the option to work for passion rather than necessity. It's about saving aggressively, investing wisely, and living frugally to reach a point where one's investments can cover living expenses indefinitely. This approach challenges the traditional lifespan of work, suggesting that life's prime shouldn't be spent entirely in pursuit of financial gain.

Communal Living: From co-housing to ecovillages, communal living arrangements advocate for sharing resources, responsibilities, and life's journey. These communities focus on sustainability, support networks, and reducing individual financial burdens through collective effort, allowing for more time dedicated to community, personal passions, and reducing the isolation that can come from a purely money-focused life.

Reevaluating Success

Beyond Financial Metrics: There's a cultural shift towards measuring success not just by bank balances but by life satisfaction, mental health, relationships, and contributions to community or environment. This involves questioning societal norms that glorify overworking and instead valuing flexibility, purpose, and personal growth.

Holistic Well-being: The concept of well-being is expanded to include physical, mental, emotional, and social health, with financial security seen as one component rather than the centerpiece of a fulfilling life.

Cultural Movements

Work-Life Balance: There's a stronger push for policies and practices that support work-life balance, like remote work, flexible hours, and the right to disconnect after work hours. This reflects a societal acknowledgment that time is a non-renewable resource, and how we spend it should align more with personal values than corporate demands.

Slow Living: Inspired by movements like "slow food" and "slow travel," slow living advocates for taking time to enjoy life's moments, prioritizing quality over quantity in all aspects of life, including work, food, and relationships.

Impact on Individuals and Society

Personal Liberation: Adopting these values can lead to personal liberation from the treadmill of constant work and consumption, allowing individuals to pursue what genuinely makes them happy or fulfilled, whether that's art, volunteering, family, or simply having more time to think and be.

Community and Environmental Benefits: A focus on communal living or minimalism can lead to less waste, lower consumption, and stronger community ties, contributing to environmental sustainability and social cohesion.

Economic Implications: While these movements might initially seem counter to economic growth models that depend on consumer spending, they could foster economies based more on quality of life services, local businesses, and sustainable practices.

Challenges in Reassessment

Cultural Resistance: Changing deep-seated beliefs about success and wealth is challenging when the dominant culture still heavily rewards and glorifies the accumulation of money.

Economic Realities: Not everyone has the same starting point or opportunities to choose such lifestyles, particularly when facing economic pressures like debt, living costs, or job insecurity.

Balancing Act: Even those who subscribe to these philosophies must navigate how to balance their ideals with practical necessities, ensuring they don't swing from one extreme (money-centric) to another (potentially neglecting financial security).

Path Forward

Education and Advocacy: Educating people about different life models through schools, media, or community workshops can normalize these alternatives.

Policy Support: Governments and businesses can support these shifts with policies like universal basic income, better labor laws, or incentives for sustainable living.

Personal Reflection: Individuals reassessing their values might find it helpful to reflect on what truly brings them joy and security, potentially leading to more intentional living.

Reassessing what we value in life is about creating a culture where money serves life rather than life serving money. It's a call to acknowledge that while financial stability is crucial, it's the means to an end, not the end itself, allowing for richer, more varied, and potentially more satisfying lives.

Conclusion

The real cost of money in modern life is multifaceted, detracting from human connections and personal fulfillment. This chapter has discussed how our societal structure, which equates money with love and security, has profound implications for individual and collective well-being. We advocate for a cultural shift where money is seen as a means to an end, not the end itself. By rethinking our relationship with money, we can foster a society that prioritizes love, community, and personal growth over mere financial accumulation. Let us reflect on how we might enrich our lives beyond economic measures, striving for a balance where money serves life, not rules it.